Zeynep Lokmanoglu

There is a story my grandmother used to tell me. I remember the beginning, but not much else.

In my head, I retell whatever I can remember of it, over and over, hoping the rest will reveal itself. I asked my cousin, my aunt, my sister, and my father. They said they remember it faintly. I suspect they remember the ghost of something else and don't know this story at all.

There’s a boy in his late teens. He leaves his village with a stick on his back and a pouch tied to the end of that stick. In the pouch are a knife, a water canteen and a set of clothes. He’s looking for adventure.

He walks for a long time, passing through green hills covered in wildflowers. He washes his face and refills his canteen with spring water. He picks berries, and sucks off their bloody juices from his fingers. He collects mushrooms and nuts in a cloth tied to his waist. He sleeps facing the stars, his head resting on his pouch. Birds sing him awake at dawn.

His lack of direction exhilarates him. But his belly is hollow and his bones are cold. He misses falling asleep by the fire after dinner with a cat on his chest. For days, he has not seen a soul. He talks to himself. He sings:

I’ve been on an endless road

My feet know the rocks as their lover

They meet and they part

They meet and they part

The old shepherd in his village taught him many songs. The boy used to think he would become a shepherd too.

He sees a town sparkling in the distance. Its foreignness intimidates him. He tells himself he’s not really that hungry.

It’s around noon and the sun is burning brightly. He retreats to a big citrus tree. He looks up and sees three oranges hanging over him. The oranges look perfectly ripe. He stares at them with big eyes. He knows many months have passed since oranges were last in season.

The rays of the sun pass through the dark branches. The oranges twinkle like jewels. He thinks of eating an orange, but the thought of its bitter taste burns his empty stomach.

He lies down to take a nap but his insides rumble. I want to feel one, he thinks.

He reaches up on tiptoe and grabs it. It comes off easily, with a snap. It is a bitter orange, he can tell from its rugged skin. He begins to peel it. Its skin is thick and gives softly. The fruit grows heavy in his hand. It begins to shake. He drops it.

As the orange hits the ground, a flashing, blinding, otherworldly ray of light shoots up from its center. From the light, a woman emerges. She’s naked and covered in pulp. Her hair is sticky, damp and reddish-brown. She’s the most beautiful woman he’s ever seen.

You should know that he has not seen many women before. Most girls in his village are married off to older men in neighboring villages and are hardly ever seen again.

Her eyes open slowly. She mumbles a single word: “Su…”

The boy closes his mouth and gulps, his back against the tree.

“Su,” she mumbles again. She looks like she’s about to faint.

“SU!” she yells, puckering her lips. Her head bends sideways and her body goes limp. In an instant, she expires. She leaves behind nothing but seeds and pulp.

The boy is terrified. He stares at the two oranges still dangling from the tree. Hours pass.

In a moment, he rouses suddenly from his daze and climbs the trunk. He reaches for one of the two remaining oranges. It doesn’t feel particularly heavy. He sniffs it. It smells like an orange. He rolls it over his palm before he punctures it and pulls on its skin.

The light is dazzling. He covers his eyes with his hands and lets the fruit fall. The same woman he saw before is now lying on the ground.

“Su.” She mutters.

The word sets him off. He pulls his canteen from his satchel.

Her limp limbs suddenly perk up and she snatches the canteen from him and gulps water down. It’s down to the last drop when her head turns, her hazel eyes ablaze.

“MORE!” She screams.

He doesn’t back away quickly enough, she grabs his arm and pulls herself up. She takes a deep breath and expires. Her sticky residue is left on his arm. His knees give and he lands on the ground.

He’s unsure how much time passes before he's able to stand again. Once he does, his mind can’t let go of a thought. There’s one last orange hanging from the tree.

My grandmother liked reminding me that the third time is always the charm.

He carefully pulls away the last orange from the tree and wraps it in his shirt. He walks to a stream and pierces the orange with his thumb in the water.

The light is so strong that it cracks the earth and splits the sky. As soon as he is able to open his eyes again, he sees the same woman he saw before.

She is on her hands and knees. Her face submerged in the pool of water. She crawls towards a small waterfall, and puts her lips on the water gushing between the rocks. The water seems to pass straight through her.

I don’t remember what happens after this. But I know my grandmother wouldn’t have told me a story that ends when a woman is brought back to life by a man.

The woman notices the boy and lifts herself out of the water.

“Thank you. I was very thirsty,” she says.

“Do you know that you came out of an orange?”

The woman scrunches up her face. “That seems right,” she says.

“I peeled two others before you. They didn’t make it.”

The woman does not respond. She has goosebumps all over.

The boy gives her his spare clothes. “You can have these,” he says. She takes them, but does not say anything.

The sun is now near the horizon. The boy digs the heel of his shoe into the ground and moves it around. “I saw a village nearby. I was thinking of stopping there for the night.”

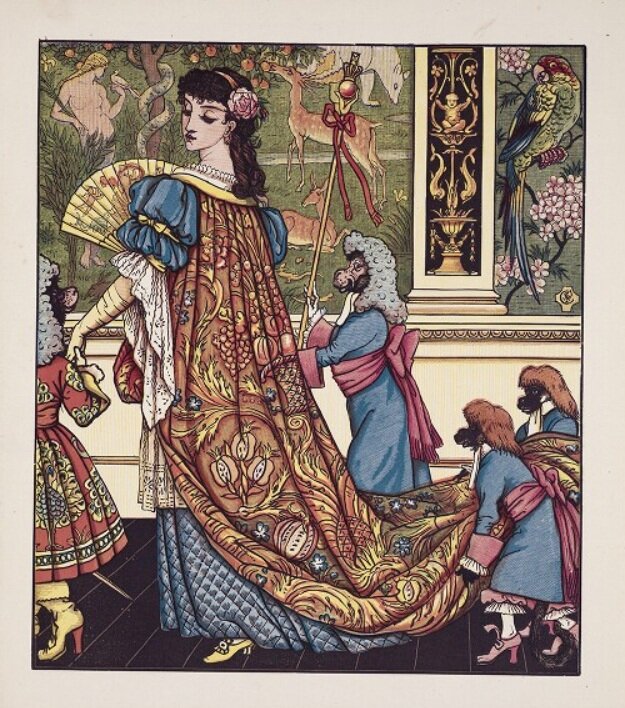

The young woman, who from this point on will be called Orange Girl, says, “I could eat something.”

They head towards the village. She walks barefoot over rocks and bushes without flinching.

When they reach the town, they are met by a guard at the gate. "Who are you, strangers?”

The boy deepens his voice. “We are on a long journey. We were hoping to find some food."

“You’re in luck,” the guard says. “Tonight is our town’s anniversary feast."

As they walk in, the guard calls out. “This town is full of respectable people, don't forget that.”

The guard calls out again, pointing into the town. “Go to the third house on the left and ask the woman there if she can spare a pair of shoes for your friend. Her name is Kadife.”

A woman with gray, waist-length hair, opens the door. There are children playing around her skirt like kittens. She looks surprised to see strangers.

“Come in,” Kadife says and leads them into a candlelit kitchen.

A shadow passes over her eyes when she sees Orange Girl’s face and her auburn hair.

She looks like she’s about to say something but then shakes her head. “You said you needed shoes?” She looks down at Orange Girl's feet. “Ah, I have just the ones.”

She disappears into a back room and returns holding a pair of leather shoes. “These should fit,” she says. “They were my sister’s.”

As they are walking away, Kadife stops them. “Maybe you should stay here with me,” she says.

“Are we not welcome?” Orange Girl asks.

“No, it’s not that...”

The sound of something shattering followed by a wail reaches them from the house. Kadife runs back, closing the door behind her.

They walk on to a large building with music and light pouring out of its windows. They are greeted at the door by a man with a sword.

“Welcome strangers,” he says to them.

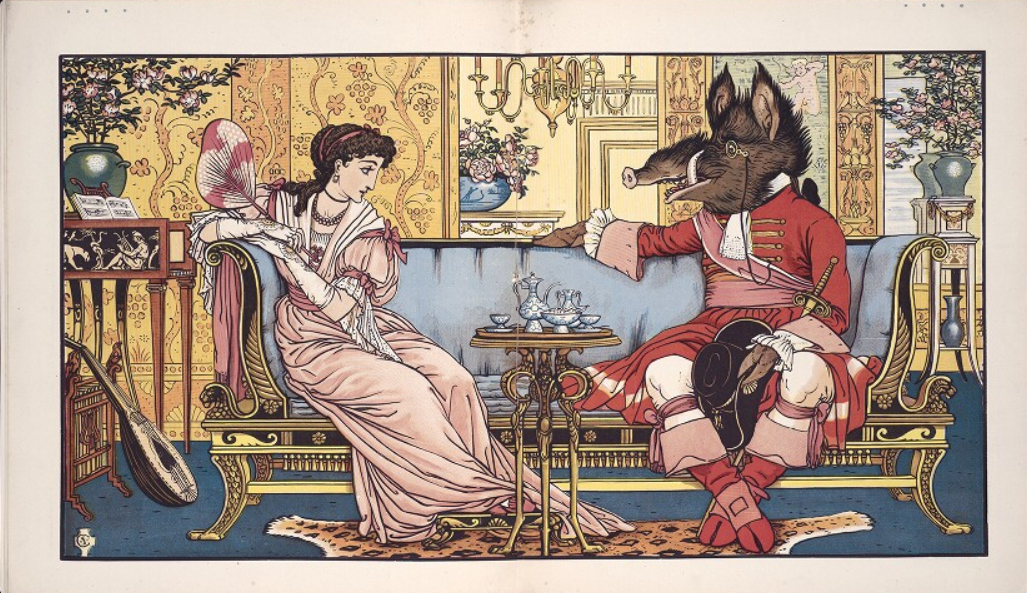

The room is full of people dressed in ornate gowns and frilly shirts. They whirl around a banquet table which is overflowing with food. Some people dance, others stand and laugh in groups. It is beautiful and smells of roast and roses.

“Where do you come from?” a woman asks. She has her hair up. Her dark yellow dress hangs off her bare shoulders.

The boy is about to answer, but instead his eyes widen. The woman waits patiently. He finally finds his words, “From a village in the Northern Mountains.”

The boy looks at the woman and then back at Orange Girl.

“Oh, that must be cold,” the woman says. She turns to Orange Girl and her red lips curve into a smile. “You’re very beautiful,” she says.

Orange Girl returns her gaze. “You look like a flower,” she says.

“Yes, I feel like a daffodil,” she says. She links arms with a man and glides away.

“You are pale,” Orange Girl says to the boy.

“Don’t you see?

"See what?”

“They all look like you!” the boy says. Orange Girl blinks blankly.

He pulls her arm gently and guides her gaze to a large silver bowl.

Orange Girl looks into the bowl, not understanding. “I see them,” she says.

A woman standing there laughs tastefully. “Oh that’s funny. No, you see yourself!”

She takes the bowl and stands next to Orange Girl. She taps her own nose with her finger. Orange Girl does the same and lets out an astonished “Oh!”

“Why do you all look the same?” The boy asks.

The woman turns to the boy and laughs drily. “It’s just the way we are.”

“But not the men,” he says.

“No, of course not.” She is growing impatient.

The boy gestures towards Orange Girl. “But she’s not from here,” he says. “Why does she look like you?”

“Well, isn’t that precious,” the woman responds. She looks around for someone else to talk to.

The boy doesn’t give in. “Do your parents also look like this?”

She furrows her brow. “Women don’t have parents,” she says. “Maybe they do where you’re from.”

She whispers to a tuxedoed man as she walks off. “They are from the villages...”

Orange Girl grabs a water jug with both hands and empties it into her mouth.

“Good evening.”

She turns around and sees a man with a long black mustache and curly locks.

“I hope you are enjoying our food,” he says. She doesn’t like the way he speaks, hitting every syllable like a blow.

“Count Gavoir.” He bows. “Where do you come from?”

The boy edges nearer to Orange Girl and opens his mouth to answer but she speaks instead: “A village North of here.”

He turns to a man. “Bernard, you’ve been to some of those villages, haven’t you?”

“Yes sir,” he says. “Always left as fast as I could.”

“Are there many women up there who look so very similar to the women of our town?”

“Never saw a single one who did.” His yellow mustache twitches over his lip.

“Surely you must see that this is very strange,” The count says.

“I look like the women here,” says Orange Girl. “I don’t see why it’s strange that someone else looks like them.”

“Because,” the count says. His face is momentarily distorted as he tries to hold back words.

A crowd of women push the men aside and surround Orange Girl and the boy.

“I don’t think she looks like me,” says a woman with a flamboyant hairdo.

The woman standing next to her laughs and says, “You don’t think any of us look like you!”

“Did you first appear in a pond by a church?” asks another woman.

The count stands in front of them. “Ladies, ladies,” he says. “Surely, this woman must be an outsider of mother-birth. And while she does look like you, I think it would be a great disservice to your great beauty to say that it is anything more than a faint resemblance.”

“I don’t know,” says another woman standing near them. “I think she’s as lovely as any of us.”

“Well, unfortunately, she must leave when the festivities end,” the Count says. A gong sounds loudly. “Ah! And there it is. The hour has come for us to part ways.”

The men attempt to shuffle the women out, but the women are hesitant.

“I wasn’t born from a mother,” Orange Girl says. Her voice surprises everyone. “I came from an orange tree not too far from the gates of this town.”

There are several gasps in the air.

“This is what happens when we let villagers in. They try to come up with fanciful stories so that we let them stay,” the count says.

A woman declares, “I think I remember something about an orange…”

“This is ridiculous,” Count Gavoir says.

Orange Girl turns to the count. “None of this feels right and you are sweating too much! I’m not going anywhere until I have an explanation.”

“Well, I should probably tell you...” Says the count as he wipes the sweat off his forehead. “An outsider who disobeys the rules of the Anniversary Feast will be sentenced to death!”

A man runs up to the count and yells. “My Count, the Orange Tree is barren and there is juice everywhere.”

“Stop speaking, idiot!” the count says.

“I meant to gather those last few oranges, but my bag was so heavy,” confesses another young man. “I thought they would just fall and rot.”

The women surround the count. Their hazel eyes turn to fire.

One of the men points a gun at the crowd and a woman smacks it away and hits him in the eye with her elbow. He screams in pain. The women take hold of the guns. They far outnumber the men.

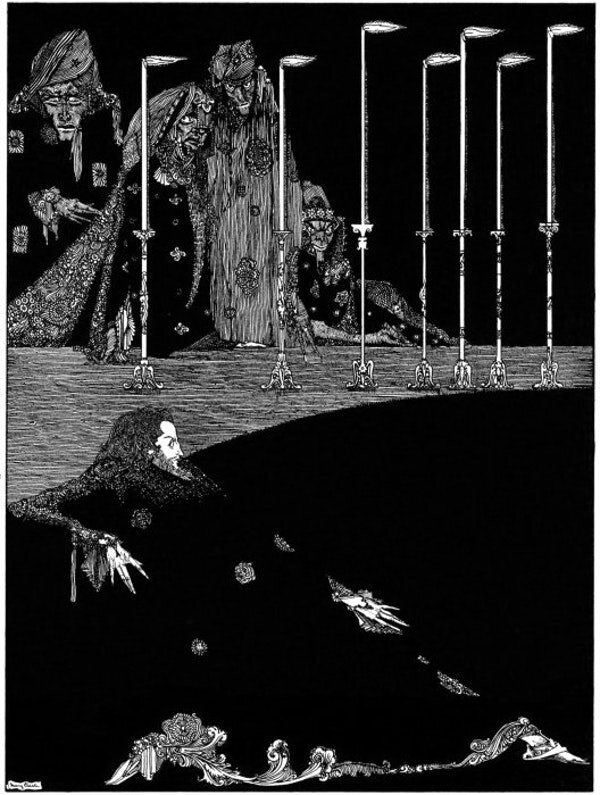

They tie the count to a chair. One holds a knife above the count’s leg, ready to stab him. “Speak,” she says.

“My ancestors did not build this town,” he mutters.

“I…When I was a young man, I worked for the King of a land far from here. My job was to document the treasures of the World. I’ve been to lands where trees were so tall they parted the clouds. I once met a man who lived in a palace made of gems guarded by an army of snakes.”

Orange Girl yawns performatively. The women tighten the count’s ropes.

The count gasps for air and his face turns purple. “If I die none of you will learn the truth.”

“Someone will speak, eventually” the women say.

“Of course you think that!” The count says. “You were not made to be smart…” Before he can say anything else, a woman raises a cauldron of bubbling soup and pours it on his lap.

As the count bellows in pain, a short stocky man with a thin mustache lets out a squeal and begins talking.

“When we came to this town, it was a happy place run by women who looked like all of you. We were told the story of the Orange Tree that gave life and the lake of wisdom that surrounded it. We were taken to the sacred tree, which was then within the town walls. One moonlit night, Count Gavoir sent one of our men to steal an orange from the tree. The women caught him and had him banished. Months later, we returned with an army. We breached the gates and attacked. It wasn’t much of a fight. It had been a peaceful place…”

Some of the women start crying.

“We killed just about everyone. We cut off the stream that fed the lake of wisdom and collected all of its water. We harvested you only when the fruit would yield you as women and we peeled you to life in a pond of our making.”

I would like to say that they killed the count, but they did not. They threw him and his men into the pond by the church, and after that they forced them out. It is unlikely they will return.

The boy and Orange Girl stay to help the women settle into their new existence. They revive the lake and bring the Orange Tree back inside the town’s walls. The women take turns guarding it.

One day Orange Girl and the boy sit with their backs to the tree. Orange Girl asks him, “Are you ready to leave?”

“It’s probably time,” he says. “You’re coming too?”

“Of course,” she says.

They leave the town with tearful goodbyes. As the town turns into a small dot behind them, Orange Girl looks at the boy.

“Do you have a name?”

The boy nods. “Ali,” he says.

“Do you like it?”

“Sure,” the Boy says. Warm thoughts of his mother and father fill his heart.

“I’ll think of one for myself,” Orange Girl says.

Zeynep Lokmanoglu grew up in Mersin, Turkey, in a home with plenty of dogs, books, and citrus trees. She studied English Literature at Brandeis University and later received an MFA in Writing from Columbia University. She’s currently working on a few short stories and a screenplay. She also started writing her novel last month, last week, and will start again tomorrow. Find her on twitter at @zlo_mo .