Francesca Merlan and Alan Rumsey

Owa, Sirku and boys building our house (1981)

At the western edge of the Nebilyer Valley, in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, there is a region known as Ku Waru, which means “cliff” or “steep stone.” The name refers to the impressive limestone cliffs that loomwhich loom over the valley.

When we first arrived at Kailge in 1981, we were struck by the intensity of people’s everyday social interaction and by how much of it continued late into the night. White people (or “red people” as they are called in Ku Waru) were completely unknown in the region until 1932, when the first Australian expedition reached the New Guinea Highlands (and found to their own surprise that, far from being uninhabited, the region had the highest population density on the island).

Notwithstanding the relative scarcity of white people (or perhaps in part because of it), Ku Waru people are fascinated with them. So when we first settled at Kailge we had a steady stream of visitors, each wanting to shake our hands and question us at length about the ways of “red people.” What do they eat? Is it true that they do not pay brideprice? That they sometimes burn their dead rather than burying them? That most of them have no gardens? How do they get along without them? That women take medicine in order not to have babies? And so forth. Interrogation would often continue into the night, by the light of our kerosene wick-lanterns or the wood fires that people tend in their low thatched houses to cook in the daytime and keep warm through the cool highland nights. Like almost all the houses in the region, the walls of our house were made of woven cane, and were thus highly permeable to sound. Conversation can easily be carried on through them. Not infrequently people try to start them with us through the walls at night.

Paulus Pai Paul Koj picking mushrooms at Kailge (1980)

Around the time of our arrival a number of organized nightly activities were taking place. The “six to six” dance was one of these activities. From our house, at night, Alan (who plays bass guitar) first heard its music. Its distinctive thump became a fixture of our night time soundscape. Alan was mystified to hear what sounded like an electric bass, given that there was no source of electric power anywhere near Kailge at that time.

The “six to six” dance belongs to a series of dances that were held in a fenced enclosure that had been set for the purpose, not far from the house where we were living. The dances were not the traditional ones of the area, performed only in the daytime, but new ones that had come in from the coast along with “string band” music sung by young men accompanied by guitars and “bamboo bass.” The string band music is performed by groups of young men singing in unison, one or more of whom would strum along on guitar. The “bamboo bass” consists of a set of hollowed out bamboo tubes or PVC plastic pipes which, by careful trimming of their length, are tuned to a set of musical intervals (usually 1-4-5) that fit the melodies of this popular genre. The pipes, about 150 to 250cm in length, are laid out horizontally, with one end supported high enough off the ground to allow it to be hit with a rubber thong. The bang produces a sound that is similar to that of an electric bass guitar.

Ruti (1982)

The first such dance that we attended quickly resolved itself into gender separation. The magistrate from the allied and neighbouring Kubuka line asked Alan to dance. He accepted, with some discomfiture. But it rapidly became clear that same-sex dancing was all there was; no mixed couples. One of this dance’s explicit aims is to go on all night, as is reflected in its name: “six to six.” This name is in English, a language which very few adults at Kailge could understand at that time. That choice of name reflected people’s sense of excitement, and proximity to something foreign, which might bring something distinctively new into their lives. Staying up all night is always felt to be portentous, indicative, even amazing and is consistent with the general emphasis we have mentioned on proactive engagement with the outside world.

Another night-time activity that developed in the 80’s, was to attend church “fellowship groups,” or “prayer groups.” These were attended exclusively by women with the exception of one, or two, young men. They met at night, in people’s homes. At the time, the only church in the area was Roman Catholic. But various Protestant denominations where active nearby, including charismatic ones. Francesca attended many of these meetings, which had a fairly standard structure of late gathering: prayer and discussion, followed by an exhortation given by one of the young men, typically a son or close relative of the women gathered in the house. These meetings thus served as “proving grounds” for young men who had yet to debut or make any significant contribution to public debate on the sing-sing ground. Their speeches to the assembled women were often harsh in tone: harangues concerning proper and improper behaviour were common. They also were delivered at length, usually a quarter of an hour or more , and—unlike men’s speeches on the sing-sing ground—were not interrupted by women, who remained recipients of the message but never emulated male speech styles during the nightly meetings.

Ruti and Francesca in jungle fowl nest (1982)

Francesca also attended the night-time meetings of the women’s “Peanut Group” a new opportunity for money-making, enterprise, and making one's name “go up.” Those who regularly came were largely from close by and thus wives and relatives of Kopia men, but a few others came from Kubuka territory across a nearby river, and sometimes from slightly further afield. The “Peanut Group” had a more distinct structure than the “Prayer Group.” There was a kilak “clerk,” always a young male, who was already in place in the meeting house, usually around 10PM when the other women would arrive. At that time, such a young man was typically the only person in the room (besides Francesca) who had a watch. (Today, many people including some women have mobile phones which some consult to see the time). He would try to enforce a starting-time, calling the women to order and haranguing them for straggling. When a sufficient number was assembled he would call roll, usually from a written list against which, at each meeting, were written small money contributions that would go towards paying off the 6 Kina notionally required in order for a member to be in good standing and to participate in the club’s activities – but such a sum was typically paid in instalments, and there was often a good deal of defaulting and promising to pay later. A large percentage of meeting time was taken up with handling these relatively small sums, entering them into the notebook, and issuing receipts. The money was to be banked in Mt Hagen for common use and projects.

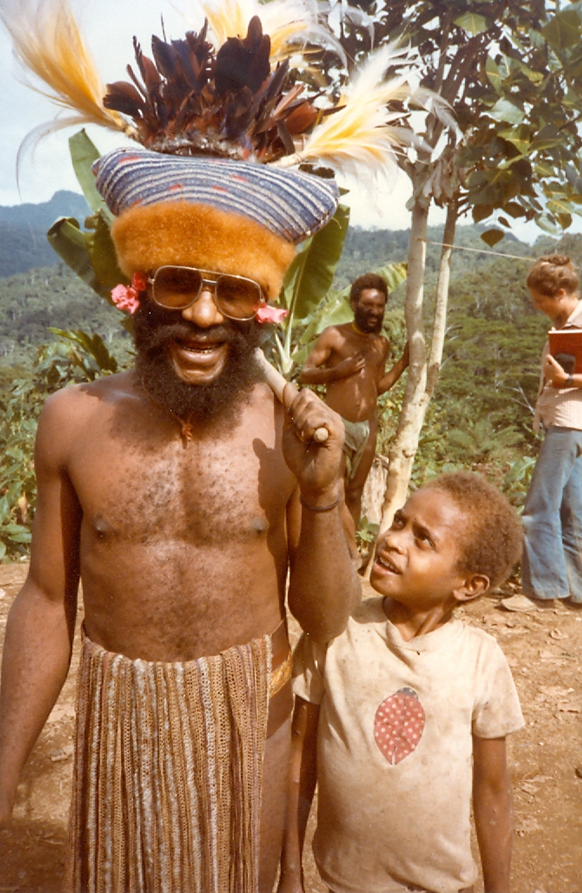

Wahgi Valley headdresses (1982)

There was also typically at least one other man in the room at each meeting, typically more senior—the Kailge Councillor, or the Kubuka Magistrate, or sometimes more than one of these. Money collection was followed by an activity called eksenda (“agenda”). This was directed to the planning of club activities – work groups, expeditions, planting of crops such as (the group’s eponymous) peanuts aimed at generating cash income, discussion of work assignments and complaints about the failure of particular people to show up for appointed work-days, the need for a club house and deliberation about where it could be built. The latter kind of topic—land-use—was felt to be weighty enough, and an aspect of local male-dominated politics, such that only senior men could ratify decisions on such matters. Senior men contributed to discussion of such things, while the kilak typically harangued the women for not contributing their money in a timely way, being bikhet (“bighead”), that is, fractious about participating in work groups, and not organizing themselves effectively. The kilak was the agad-fly and source of running moral and practical critique of women’s behaviour. The women typically bore such hectoring, even though the usual kilak was a relatively young man and the son of one of the senior women who always attended.

Despite all this monitoring, club meetings had a frisson of excitement about them, associated with the handling of money and the planning of events which could allow women to participate on the more public stage, for example, of the Hagen show. Excitement for the women also derived from a sense of competitiveness among similar groups in the valley: women typically had heard something about what other such groups were doing, and there were always rumours about others’ plans and savings. Such meetings often lasted past midnight or even later if there were some plan afoot; but like everyone else at Kailge, women had no problem moving about at night, and would walk home along Kailge’s paths. There was no suggestion of this being improper or dangerous.

Kailge entertainment at night, Wapi, Wai, John (1980)

As we settled in at Kailge during 1982-3 and were less of a novelty we became more familiar with the people’s daily routines, including the kinds of things they did at night when they were not engaged in any special activities such as fellowship or work-group meetings, or visiting newly arrived “red people.” In order to picture those more quotidian activities you have to bear in mind that at Kailge most of people’s everyday subsistence needs are met by local agricultural production organized at the level of households, with the lion’s share of the work being done by women. Up until the 1970s or so men and women slept in separate houses, the men with other men and older boys (most of them usually of their own clan), and the women with their younger children. Nowadays married couples generally live together along with their children and sometimes grandchildren and other close kin and in-laws. Most families own pigs, anywhere between one or two. At night the pigs are kept in stalls, formerly located within the women’s houses, and now in separate shelters within earshot of the house.

Nebilyer Valley Scene

The organization of the daily domestic routine into daytime and night time is strongly conditioned by the imperatives of pig-tending and the growing of sweet potatoes, the main staple crop in the region. Early each morning the pigs are taken out to pasture, sometimes in fenced enclosures, but more often tethered ropes to posts driven into the ground which they range around for the whole day, snuffling for fodder. Given the danger of theft or escape, an absolute requirement of pig husbandry is that the animals be brought back to their stalls every day before dark. An almost equally urgent requirement is for enough sweet potatoes to be harvested and brought back from the gardens every day, not only to feed all the people in the household, but also to feed to the pigs as a supplement, without which they would never grow fat.

Because Kailge is close to the equator (ca. 7 degrees south) sunrise and nightfall happen quickly, with very little seasonal variation in the times at which they occur. Since the pigs are seldom brought back long before nightfall this means that there is a very regular transition phase between day and night which begins with the return of the pigs to their stalls. This is followed by the cooking of the evening meal, usually consisting of sweet potatoes (or, on special occasions, store-bought rice), greens, and small amounts of tinned fish or meat. (Pigs are slaughtered and eaten only rarely, on special occasions such as inter-group ceremonial exchange events or funerals).

Thomas Nekij festival Ulka

Dinner is eaten around the fire, which burns in a stone fireplace in the middle of the front room of the house. It is usually a time of animated conversation, which often continues well into the night. This often includes extensive story-telling, about events of the day, others in which the narrator has been involved, and yet others which he or she has only heard about. Some of these stories are more-or-less traditional ones belonging to established narrative genres called kange and temani or some poems. Other verbal genres that people engage in during this time were games played between young children and adults or older children.

On a trip to Kailge in 2015, Paul Kaya and Pes Onga explained to us two games that they (both in their forties?) played as children. People still play these games, they said – but we had not seen them played within the household circle of our earlier compound, neither during our longer stays of the 1980s, nor more recently in the household compound we now share with Pes’ brother and other close relatives.

Koi and Yaya (1980)

The first game is called suril-saril, after the characteristic ditty featured in it. The game is typically played by people at night before sleep, and very deliberately by parents in order to get children to settle and go to sleep. Paul and Pes illustrated how it goes. A lead player chants siril saril siril saril and then names a person in a given house compound, usually starting with a father or key person, and followed byby the mother, then the children and others. Each time the lead-player names a person, the other players signal recognition and approval by saying: Nopel. (None of these words has any literal meaning; Pes glossed nopel as “OK.”) The turn switches back to the lead player, who names another person; then back to the nopel-sayer. Together and cooperatively, they name all those who regularly live in a given house compound. Pes and Paul demonstrated this to us as follows for the house compound of John Ongka, our closest neighbour and Pes’ older brother.

Pes: siril-saril siril-saril John Ongka.

Paul: Nopel.

Pes: siril-saril siril-saril Wapi.

Paul: Nopel.

Pes: siril-saril siril-saril Alex.

Paul: Nopel.

Pes: siril-saril siril-saril Justina.

Paul: Nopel.

Pes: siril-saril siril-saril Lewa.

Paul: Nopel.

Pes: siril-saril siril-saril Augusten.

Paul: Nopel.

Pes: siril-saril siril-saril Jesi.

Paul: Nopel.

Wapi is John’s wife; Alex is an older son who still lives in the house compound, while their eldest, Stanley, has built his own house and lives at Kailge with his wife, hence is not mentioned; Justina is John and Wapi’s eldest daughter; Lewa and Jesi another daughter and son of theirs; and Augusten is the child of another daughter who lives in Jiwaka, while Augusten stays at Kailge.

Having completed a particular house compound roster, the lead player then moves on to another household. Pes and Paul demonstrated this for us by saying:

Pes: Tepi kiripul polup pensip pupu.

Literally, this can be glossed “fire hearth thrust put go,” with all verb stems marked with a final –p(u), signalling first person plural. The force of the phrase is “we sum up this hearth and move on to another.” The lead player then begins by naming another key householder in the next compound:

new forms of night entertainment

Pes: siril-saril siril-saril Lep.

Paul: Nopel.

Pes: siril-saril siril-saril Mawa.

Paul: Nopel.

Pes: siril saril siril-saril Joelle.

Paul: Nopel.

Pes: siril-saril siril-saril Belinda.

Paul: Nopel.

Pes: siril saril siril-saril Susanne.

Pes: siril-saril siril-saril kang kelayl.

Paul: Nopel.

Here Pes moved on to the nearby household of John Ongka’s brother Lep. He named Lep, his wife Mawa, their daughters, and then, finally, unable to recall the name of the last boy child Pes knows to live there, he simply smoothly said kang kelayl “small boy,” to which Paul responded: Nopel (also aware of the boy, but probably also not knowing his name). At that point Pes moved on to the house compound of another brother living nearby, Michael. And so on, until sleep set in.

For us outsiders learning the game, one of its interesting features was how directional demonstrative pronouns were deployed in those phrases signalling movement to another house compound. The location of the players is treated as “first” origo , but then each subsequent household establishes the next origo from which further movement is expressed, this provides an opportunity to observe the rather tricky Ku Waru directionals with respect to known locations. For example, having summed up the household of a tribal brother, Opis, and his wife Julie, who live by themselves, Pes moved on:

Pes: yabu-tal kaniyl tepi kiripul pensip pupu wikid Lorenz

Those two people [Opis and Julie], tying up their hearth and going upwards, [to the house of] Lorenz.

This provides an example of the use of wikid, which typically means “upslope” from the present origo. And next, from Opis’s house:

Pes: yabu akiyl tepi kiripul pensip uru okum-kilyo takatakan mad mad obu Walyo kansiyl

Those folks [Lorenz and his family], tying up their hearth, sleep’s coming on!, slow and steady coming down down (to) Walyo council’s [household]

This movement produces an example of mad which usually means “downslope.” And, as people do, Pes produces running commentary on and incentive to—sleep! Which is, after all, the point of the exercise from the parental point of view. What a nice way to do genealogies, or at least house censuses!

The second game is also called by the ditty which introduces it: nopinga napinga, no more meaningful than siril-saril. But it signals that the lead player is going to pose a riddle:

Ruti (1982)

Paul: nopinga napinga nopinga napinga kuduyl-te

‘Nopinga napinga, one red thing’

Kung kuduyl-te pensikumul, na pilyikr-alyi, oba

‘we yard up a red pig, I believe, that is…’

Posing the riddle thus, Paul proposes that what he is thinking of can be thought of as a red pig, inside an enclosure. The second player:

Pes: Mel-te poket-na pinsin, ilyi-d nyikin

‘You put something in your pocket, you’re talking about that’

Paul rejects that guess, and Pes says:

Pes: takan molui, takan molui, pilyab pilyab pilyab

‘Be quiet! Be quiet! Let me think, think think’

And he comes up with it...

Pes: Nu-nga anubilayl gu-kn pala telym I kana ekepu na pilyikir pilyikir

Your tongue, (with) your teeth making the fence, see, now, I got it I know it’

Another riddle posed was that of some people cleaning a bird’s nest: what could that be? A first guess was that this referred to flies eating the buds on sweet potato (kaukau pudi), but this was rejected. Finally, the correct answer: the riddle was about pengi lema “head lice” being picked by someone for another.

Alan Rumsey and Francesca Merlan are anthropologists. They both teach at the Australian National University.