Lucia Berlin

Anytime Laura thought about Decca, she saw her as if in a stage set. She had met Decca when she and Max were still married, many years before Laura married him. The house on High Street, in Albuquerque. Beau had taken her. Through the wide-open door into a kitchen with dirty pots and pans, dishes and cats, open jars, plates of runny fudge, uncapped bottles, cartons of takeout Chinese, through a bedroom, bumping into piles of clothes, shoes, stacks of magazines and newspapers, mesh sweater dryers, tires. Dimly lit center stage a bay window with frayed saffron nicotine-stained shades. Decca and Max sat in leather chairs, facing a miniature TV on a stool. The table between them held an enormous ashtray full of cigarette butts,

a magazine with a knife and a pile of marijuana, a bottle of rum and Decca’s glass. Max wore a black velour bathrobe, Decca a red silk kimono, her dark hair loose and long. They were stunning to look at. Stunning. Their presence hit you physically, like a blow.

Decca didn’t speak but Max did. His thick-lashed heavy-lidded stoned dark eyes looked deep into Laura’s. He rasped, “Hey, Beau, what’s happening?" Laura couldn’t remember anything after that. Maybe Beau asked to borrow the car or some money. He was staying with them, on his way to New York. Beau was a saxophone player she had met by chance, walking her baby in his stroller on Elm Street.

Decca. How come aristocratic Englishwomen and upper class American women all have names like Pookie and Muffin? Have they kept the names their nannies called them? There is a news reporter on NBC called Cokie. No way is Cokie from a nice family in Ohio. She is from a fine old wealthy family. Philadelphia? Virginia? Decca was a B—, one of the best Boston families. She had been a debutante, studied at Wellesley, was partly disinherited when she eloped with Max, who was Jewish. Years later, Laura too had been disinherited when her family heard of her own elopement with Max, but they relented when they realized how wealthy he was.

Decca called around eleven that night. Laura’s sons were asleep. She left them a note and Decea’s number in case one of them woke up, said she’d be back soon.

The reason it always seems like a stage set, she told herself, is because Decca never locks her doors and never gets up to answer the doorbell or a knock. So you just go in and find her in situ, stage right, in a dim light. At some point, before she sat down and started drinking, she had lit a piñon fire, candles in niches and kerosene lanterns whose soft lights catch now in her cascading silken hair. She wears an elaborately embroidered green kimono over a still lovely body. Only close up can you see that she is over forty, that drink has made her skin putty, her eyes red.

It is a large room in an old adobe house. The fire reflects in the red tile floor. On the white walls are Howard Schleeter paintings, a Diebenkorn, a Franz Kline, some fine old carved Santos. Underwear dangles from a John Chamberlain Sculpture. Over the baby's crib in a corner hangs a real Calder mobile. If you looked you could see fine Santo Domingo and Acoma pots. Old Navajo rugs are hidden beneath stacks of Nations, New Republics, I.F. Stone Newsletters, New York Times, Le Monde, Art News, Mad Magazines, pizza cartons, Baca’s takeout cartons. The mink-covered bed is piled with clothes, toys, diapers, cats.

Empty straw-covered jugs of Bacardi lie on their sides around the room, occasionally spinning when cats bat at them. A row of full jugs stands next to Decca’s chair, another by the bed. Decca was the only female alcoholic Laura knew that didn’t hide her liquor. Laura didn’t admit to herself yet that she drank, but she hid her bottles. So her sons wouldn’t pour them out, so she wouldn’t see them, face them.

If Decca was always set on stage, in that great chair, her hair in the lamplight shining, Laura was particularly good at entrances. She stands, elegant and casual in the doorway, wearing a floor-length Italian suede coat, in profile as she surveys the room. She is in her early thirties, her prettiness deceptively fresh and young.

“What the fuck are you doing here?” Decca says.

“You called me. Three times, actually. Come quick, you said.”

“I did?” Decca pours some more rum. She feels around under her chair and comes up with another glass, wipes it out with her kimono.”

“I called you?” She pours a big drink for Laura, who sits in a chair on the other side of the table. Laura lights one of Decca’s Delicados, coughs, takes a drink.

“I know it was you, Decca. Nobody else calls me ‘Bucket Butt’ or ‘Fat-assed sap.’”

“Must have been me,” Decca laughs.

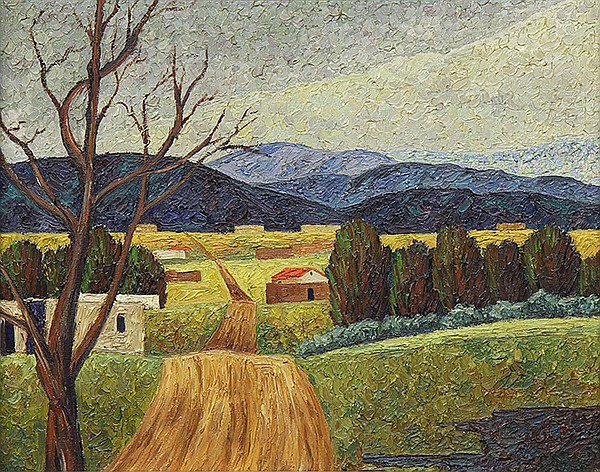

Howard Schleeter, Taos Valley, New Mexico, 1937

Howard Schleeter, Legendary Almanac, 1947

Howard Schleeter, Landscape, 1936

“Well, you learned how to drink, anyway. I remember when you two were first married. I offered you a martini and you said, ‘No, thanks. Alcohol gives me vertigo.’”

“It still does."

“Weird how both his wives ended up lushes.”

“Weirder still we didn’t end up junkies.”

"I did,” Decca says. “For six months. I got into drinking trying to get off of heroin.”

“Did using make you closer to him?”

“No. But it made me not care.” Decca reaches over to an elaborate stereo system, changes the Coltrane tape to Miles Davis. Kind of Blue. “So our Max is in jail. Max won’t handle jail in Mexico.”

“I know. He likes his pillowcases ironed.”

“God, you’re a ditz. Is that your assessment of the situation?”

“Yeah. I mean if he’s like that about pillowcases, imagine how hard everything else will be. Anyway, I came to tell you that Art is taking care of it. He’s sending down money to get him out.”

Decca groans. “Christ. it’s all coming back to me. Guess how the money is getting there? With Camille! Beau was on the plane with her to Mexico City. He called me from the airport. That’s why I called you. Max is going to marry Camille!”

“Oh, dear.”

Decca pours them both more rum.

"Oh, dear? You’re so lady-like it makes me sick. You’ll probably send them crystal. You’re smoking two cigarettes.”

“You sent us crystal. Baccarat glasses.”

“I did? Must have been a joke. Anyway, Camille told Max they’re going to Acapulco for their honeymoon. Just like you did.”

“Acapulco?” Laura stands up, takes off her coat and throws it on the bed. Two cats jump off. Laura is wearing black silk pajamas and slippers. She is weaving, either from emotion or so much rum. She sits.

“Acapulco? She says this sadly.

“I knew that would get you. Probably to the same suite at

the Mirador. The scent of bougainvillea and hibiscus wafting into their room.”

“Those flowers don’t smell. Nardos would be wafting.” Laura holds her head in her hands, thinking.

“Stripes. Stripes from the sun through the wooden shutters.”

Decca laughs, opens a new jug of rum and pours.

“No, Mirador is too quiet and old for Camille. He'll take her to some jive beach motel with a bar in the swimming pool, the stools underwater, umbrellas in the coconut drink. They’ll drive around town in a pink jeep with fringe on it. Admit it, Laura. This pisses you off. A dumb file clerk. Tawdry little tart!"

“Come on, Decca. She's not so bad. She’s young. The same age as each of us were when we married him. She’s not exactly dumb."

This fool is genuinely kind, Decca thought. She must have been so kind to him.

“Camille is dumb. God, but so were you. I knew you loved him, though, and would give him sons. They are beautiful, Laura."

“Aren’t they?’

I am dumb, Laura thought, and Decca is brilliant. He must have missed Decca a lot.

"I wanted a baby so badly," Decca says. “We tried for years. Years. And fought over it, because I was so obsessed, each of us blaming the other. I could have killed that ob/gyn Rita when she had his baby.”

“You know she researched all over town and picked him.

She didn’t want a lover, just a baby. Sappho. What a name, no?”

“Weird. Weirder is years after we’re divorced and I’m forty years old, I get pregnant. One night, one damn night, no maybe ten blooming minutes in mosquito-infested San Blas I fuck an Australian plumber. Bingo."

"Is that why you named your baby Melbourne? Poor kid. Why not Perth? Perth is pretty.” Unsteadily, Laura gets up and goes to look at the child. She smiles and covers him.

“He’s so big. Wonderful ginger hair. How is he doing?”

“He’s great. He’s a pretty damn great kid. Starting to talk.”

Decca stands, stumbles slightly as she crosses the room to check on the child and then goes to the bathroom. Laura finishes her drink, starts to stand and go home.

“I’ll be going now,” she says to Decca when she comes back.

“Sit down. Have another drink.” She pours. They are drinking from ludicrously small tea cups considering how often they are refilled.

"You don’t seem to grasp the seriousness of this situation. Now, I’m fine, set for life. I got a huge divorce settlement plus I have family money. What about any inheritance for your children? This woman will wipe him out. You were a fool not to get child support. Blithering fool.”

“Yeah. I thought I could support us. I had never had a job before. His habit was eight hundred dollars a day and he was always wrecking cars. So I just got money for their college funds. You want to know the honest truth? I didn’t think he could possibly live much longer.”

Decca laughs, slapping her knee. “I knew you didn’t! What’s her name, she didn’t want any child support either. 0ld lawyer Trebb called me after your divorce came through. He wanted to know why it was that all three of us women had gigantic life insurance policies from Max.”

Decca sighs, lights up a fat joint that had been lying on the table. It sputters and crackles; little flames make three big holes in her lovely kimono. One right in the middle of the Italy-shaped rum stain. She beats on them, coughing, until the fires are out, passes the joint to Laura. When Laura inhales, she too creates a little shower of sparks that burn holes in her silk top.

“At least he taught me how to de-seed weed,” she says, talking funny throw the smoke.

“So,” Decca continues. “he’ll be clean when he gets out. Alive and well in Acapulco. I gave him the best years of my life and now look. He’s alive and well in Acapulco with a car-hop.” Decca’s speech is slurred now, her nose running as she wails, “The best years of my life!”

“Hell, Decca, I gave him the worst years of my life!”

Richard Diebenkorn, Figure with Hat, 1967

Richard Diebenkorn, Girl on the Beach, 1967

Richard Diebenkorn, Interior with Ocean View, 1957

The two women find this hysterically funny, slap at each other, hold their sides, stomp their feet and knock over the ashtray, laughing so hard. Laura starts to take a drink but spills it down the front of her pajamas.

“Seriously. Decca," Laura says. “This may be a really good thing. I hope they’re happy. He can show her the world. She will adore him, take care of him.”

“Take him to the cleaners. Is she a floozy or what? Tacky car-hop.”

“You’re dating yourself. She’s more of a Clinique salesgirl, I’d say. You know she was once Miss Redondo Beach?”

“You have style, B.B. A subtle, lady-like bitch. You’ll act simply delighted for the nuptial pair. Probably throw rice at them. So tell me now, how does it really feel, thinking of them in Acapulco? Imagine. Sunset now. The sun is making a green dot and vanishing. ‘Cuando Calienta el Sol' is playing. Lots of throbbing saxophone, maracas. No, the music is playing. ‘Piel Canela' now but they're still in bed. She’s asleep, fired after sun and water-skiing. Steamy sweaty sex. He lies full against her back. He grazes the hack of her neck with his lips, leans, chews on her ear, breathing.”

Laura spills some of a freshly poured drink down her shirtfront. “He did that to you?” Decca passes her a towel to dry herself with.

“Bucket-Butt, you think you've got the only ear lobe in the world?” She grins, enjoying this now. “Then he’d brush your breast with the palm of his hand, right? You’d groan and turn toward him. Then he’d catch your head in. . .”

“Stop it!”

They’re both depressed now. They smoke and drink with the elaborately careful slow motion of the very drunk. Cats come near them, weaving but they both absentmindedly kick them away.

“At least there weren't any before me,” Decca said.

“Elinor. She still calls him, middle of the night. Cries a lot.”

“She doesn't count. She was his student at Brandeis. One rainy intense weekend at Truro. Her family called the dean. End of romance and teaching career.”

“Sarah?"

“You mean Sarah? His sister Sarah? You're not so dumb, BB. Sarah is our biggest rival of all. I never said it out loud though. Do you think they ever actually made love?”

“No, of course not. But they are so close. Fiercely close. I don’t think anybody could adore him like she does.”

"I was jealous of her. God, I was jealous of her.”

“Decca. Listen! Oh, wait a minute. I’ve got to pee.” Laura stands, totters, reels across the room into the bathroom. Decca hears her fall, the crack of head against porcelain.

“You okay?”

“Yeah.”

Laura returns, crawling on all fours to her chair.

“Life is fraught with peril,” she giggles. There is already a big blue goose bump on her forehead.

“Listen, Decca. There is nothing to worry about. He’ll never marry Camille. Maybe he said that to get her down there. But he won't. I’ll bet you a billion dollars. And you know why?”

“Yep. I’ve got it. Sister Sarah! She’ll never get past old Sarah."

Decca had been tying her hair up with an elastic, high on top of her head so it looked like a crooked palm tree. Laura’s hair had come loose from her chignon, so a hunk just flops out of one side of her head. They sit smiling stupidly at one another in their burned wet clothes.

“That’s right. Sarah really likes you and me. You know why?”

“Because we are well-bred."

“Because we are ladies.” They toast each other with a fresh drink, laughing uproariously, kicking the floor.

“It’s true," Decca says. “Although perhaps at this moment we’re not quite at our best. So, tell me, were you jealous of Sarah too?”

“No," Laura says. “I never had a real family. She helped me feel part of one. Still does, and she loves the boys. No, I was jealous of the dope dealers. Joni, Beto, Willy, Nacho.”

“Yeah, all the pretty punks."

“They always found us. A year and a half clean. Beto found us in Chiapas, at the foot of the church on the hill. San Cristobal. Streaks of rain on his mirror sunglasses.”

“You ever know Frankie?"

“I knew Frankie. He was the sickest”

“I saw his dog die, once when he got busted. He even had his toy poodle strung out on junk."

“I once stabbed a connection, in Yelapa. I didn’t even hurt him, really. But I felt the blade go in, saw him bleed."

Decca is crying now. Sad sobs, like a child’s. She puts on Charlie Parker with Strings. “April in Paris.”

“Max and I were in Paris in April. Rained the whole damn time. We were both pretty lucky, Laura, and drugs ruined it all. I mean for a short time we had everything a woman could want. Well, I knew him in his golden years. Italy and France and Spain. Mallorca. Everything he did turned to gold. He could write, play saxophone, fight bulls, race cars.” She pours them more rum.

Laura can’t express herself. “I knew him when, when he was . . .”

“You almost said happy, didn’t you. He was never happy."

“Yes, he was. We were. No one ever was so happy as we were."

Decca sighs, “That might be true. I thought it. seeing you all together. But it wasn’t enough for him.”

New York Daily Mirror front page article, August 6, 1962

“Once we were in Harlem. Max and a musician friend went into the bathroom to fix. The man’s wife looked at me, across the kitchen table, and she said, “There our men go, to the lady in the lake.” Maybe we were wrong, Decca. Hubris or something, wanting to mean too much to him. Maybe this girl, what’s her name? Maybe she’ll just be there.

Decca had been talking to herself. Aloud she said, “No one could ever ever mean so much to me. Have you met any man who can touch him? His mind? His wit?”

“No. And none of them are so kind or sweet, like how he cries at music, kisses his sons goodnight.”

Both women are sobbing now, blowing their noses. “I get relay lonesome. I try to meet men,” Laura says. “I even joined the ACLU.”

“You what?”

“I even went to the Sundowner for Happy Hour. But all the men just got on my nerves.”

“That’s it. Other men jar after Max. They say ‘you know’ too much or repeat the same stories, laugh too loud. Max never bored, Max never jarred.”

“I went out with this pediatrician. A sweet guy who wears bow ties, flies kites. The perfect man. Loves children, healthy, handsome, rich. He jogs, drinks rosé wine coolers.” The women roll their eyes. “OK, so I have it all set up. The children are asleep. I’m in white chiffon. We’re at the table on the terrace. Candles. Stan Getz and Astrud Gilberto Bossa Nova. Lobster. Stars. Then Max shows up, drives up on the lawn in a Lamborghini. Wearing a white suit. He gives us a little wave, goes in to see the kids, says something idiotic like he loves to look at them when they’re sleeping. I lost it. Smashed the rosé wine cooler pitcher on the bricks, threw the plates of lobster, smash, smash, salad plates, smash. Told the guy to hit the road.”

“Which he did, right?”

“Right.”

“See, Laura, Max would never have left. He’d have said something like, ‘Honey, you need some loving,’ or he’d start throwing plates and dishes too until you were both laughing.”

“Yeah. Actually he sort of did when he came out. He smashed some glasses and a vase of freesia but he rescued the lobster and we ate it. Sandy. He just grinned and said, ‘That pediatrician is hardly an improvement.”

“There’s never been a man like him. He never farted or belched.”

“Yes, he did, Decca. A lot.”

"Well, it never got on my nerves. You just came over to upset me. Go home!"

“Last time you told me to go home you were in my house.”

“I did? Hell, I’ll go home then.”

Laura gets up to leave. She lurches toward the bed to get her coat, stands there, getting her bearings. Decca comes up behind her, embraces her, touches her neck with her lips. Laura holds her breath, doesn’t move. Sonny Rollins is playing “In Your OwnSweet Way.” Decca leans, kisses Laura on the ear.

“Then he brushes your nipple with the palm of his hand.”

She does this to Laura. “Then you turn to him and he holds your head in both hands and kisses you on the mouth.” But Laura doesn’t move.

“Lie down, Laura.”

Laura stumbles, slides down onto the mink-covered bed. Decca blows out the lantern and lies down too. But the women are facing away from each other. Each is waiting for the other to touch her the way Max did. There is a long silence. Laura weeps, softly, but Decca laughs out loud, whacks Laura on the buttock.

“Good night, you fat-assed sap.”

In just a short time. Decca is asleep. Laura leaves quietly, arrives home and showers, dresses before her children wake up.

Franz Kline, Green Cross, 1956

Franz Kline, Opustena, 1961

Franz Kline, Le Gros, 1961

Lucia Berlin was an American short-story writer. She was born in Alaska in 1936, and she died, at 68, in California.